Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid

arthritis (RA) is a chronic multisystem disease of unknown cause. Although

there are a variety of systemic manifestations, the characteristic feature of

RA is persistent inflammatory synovitis, usually involving peripheral joints in

a symmetric distribution. The potential of the synovial inflammation to cause

cartilage destruction and bone erosions and subsequent changes in joint

integrity is the hallmark of the disease. Despite its destructive potential,

the course of RA can be quite variable. Some patients may experience only a

mild oligoarticular illness of brief duration with minimal joint damage,

whereas others will have a relentless progressive polyarthritis with marked

functional impairment.

Epidemiology and Genetics

The

prevalence of RA is approximately 0.8% of the population (range 0.3 to 2.1%);

women are affected approximately three times more often than men. The

prevalence increases with age, and sex differences diminish in the older age

group. RA is seen throughout the world and affects all races. However, the

incidence and severity seem to be less in rural sub-Saharan Africa and in

Caribbean blacks. The onset is most frequent during the fourth and fifth

decades of life, with 80% of all patients developing the disease between the

ages of 35 and 50. The incidence of RA is more than six times as great in 60-

to 64-year-old women compared to 18- to 29-year-old women.

Family

studies indicate a genetic predisposition. For example, severe RA is found at

approximately four times the expected rate in first-degree relatives of

individuals with disease associated with the presence of the autoantibody,

rheumatoid factor; approximately 10% of patients with RA will have an affected

first-degree relative. Moreover, monozygotic twins are at least four times more

likely to be concordant for RA than dizygotic twins, who have a similar risk of

developing RA as nontwin siblings. Only 15 to 20% of monozygotic twins are

concordant for RA, however, implying that factors other than genetics play an

important etiopathogenic role. Of note, the highest risk for concordance of RA

is noted in twins who have two HLA-DRB1 alleles known to be associated with RA.

The class II major histocompatibility complex allele HLA-DR4. (DRB1*0401) and

related alleles are known to be major genetic risk factors for RA. Early

studies showed that as many as 70% of patients with classic or definite RA

express HLA-DR4 compared with 28% of control individuals. An association with

HLA-DR4 has been noted in many populations, including North American and

European whites, Chippewa Indians, Japanese, and native populations in India,

Mexico, South America, and southern China. In a number of groups, including

Israeli Jews, Asian Indians, and Yakima Indians of North America, however,

there is no association between the development of RA and HLA-DR4. In these

individuals, there is an association between RA and HLA-DR1 in the former two

groups and HLA-Dw16 in the latter. Molecular analysis of HLA-DR antigens has

provided insight into these apparently disparate findings. The HLA-DR molecule

is composed of two chains, a nonpolymorphic ![]() chain

and a highly polymorphic

chain

and a highly polymorphic ![]() chain.

Allelic variations in the HLA-DR molecule reflect differences in the amino

acids of the

chain.

Allelic variations in the HLA-DR molecule reflect differences in the amino

acids of the ![]() chain,

with the major amino acid changes occurring in the three hypervariable regions

of the molecule. Each of the HLA-DR molecules that is associated with RA has

the same or a very similar sequence of amino acids in the third hypervariable

region of the

chain,

with the major amino acid changes occurring in the three hypervariable regions

of the molecule. Each of the HLA-DR molecules that is associated with RA has

the same or a very similar sequence of amino acids in the third hypervariable

region of the ![]() chain

of the molecule. Thus the

chain

of the molecule. Thus the ![]() chains

of the HLA-DR molecules associated with RA, including HLA-Dw4 (DR

chains

of the HLA-DR molecules associated with RA, including HLA-Dw4 (DR![]() 1*0401),

HLA-Dw14 (DR

1*0401),

HLA-Dw14 (DR![]() 1*0404),

HLA-Dw15 (DR

1*0404),

HLA-Dw15 (DR![]() 1*0405),

HLA-DR1 (DR

1*0405),

HLA-DR1 (DR![]() 1*0101),

and HLA-Dw16 (DR

1*0101),

and HLA-Dw16 (DR![]() 1*1402),

contain the same amino acids at positions 67 through 74, with the exception of

a single change of one basic amino acid for another (arginine

1*1402),

contain the same amino acids at positions 67 through 74, with the exception of

a single change of one basic amino acid for another (arginine ![]() lysine)

in position 71 of HLA-Dw4. All other HLA-DR

lysine)

in position 71 of HLA-Dw4. All other HLA-DR ![]() chains

have amino acid changes in this region that alter either their charge or

hydrophobicity. These results indicate that a particular amino acid sequence in

the third hypervariable region of the HLA-DR molecule is a major genetic

element conveying susceptibility to RA, regardless of whether it occurs in

HLA-DR4, HLA-Dw16, or HLA-DR1. It has been estimated that the risk of

developing RA in a person with HLA-Dw4 (DR

chains

have amino acid changes in this region that alter either their charge or

hydrophobicity. These results indicate that a particular amino acid sequence in

the third hypervariable region of the HLA-DR molecule is a major genetic

element conveying susceptibility to RA, regardless of whether it occurs in

HLA-DR4, HLA-Dw16, or HLA-DR1. It has been estimated that the risk of

developing RA in a person with HLA-Dw4 (DR![]() 1*0401)

or HLA-Dw14 (DR

1*0401)

or HLA-Dw14 (DR![]() 1*0404)

is 1 in 35 and 1 in 20, respectively, whereas the presence of both alleles puts

persons at an even greater risk. The lack of association of HLA-DR4 and RA in

certain populations is explained by the major member of the DR4 family found in

that population. HLA-DR4 is a family of closely related, serologically defined

molecules, including HLA-Dw4, -Dw10, -Dw13, and -Dw15. Different members of the

HLA-DR family of molecules are found to predominate in different ethnic groups.

Thus, in HLA-DR4-positive North American whites, HLA-Dw4 and -Dw14 are the most

frequent, whereas HLA-Dw15 is most frequent in Japanese and southern Chinese.

Each of these is associated with RA. By contrast, HLA-Dw10, which is not

associated with RA and contains nonconservative amino acid changes in positions

70 and 71 of the

1*0404)

is 1 in 35 and 1 in 20, respectively, whereas the presence of both alleles puts

persons at an even greater risk. The lack of association of HLA-DR4 and RA in

certain populations is explained by the major member of the DR4 family found in

that population. HLA-DR4 is a family of closely related, serologically defined

molecules, including HLA-Dw4, -Dw10, -Dw13, and -Dw15. Different members of the

HLA-DR family of molecules are found to predominate in different ethnic groups.

Thus, in HLA-DR4-positive North American whites, HLA-Dw4 and -Dw14 are the most

frequent, whereas HLA-Dw15 is most frequent in Japanese and southern Chinese.

Each of these is associated with RA. By contrast, HLA-Dw10, which is not

associated with RA and contains nonconservative amino acid changes in positions

70 and 71 of the ![]() chain,

is most common in Israeli Jews. Therefore, HLA-DR4 is not associated with RA in

this population. In certain groups of patients, there does not appear to be a

clear association between HLA-DR4-related epitopes and RA. Thus, nearly 75% of

African American RA patients do not have this genetic element. Moreover, there

is an association with HLA-DR10 (DRB1*1001) in Spanish and Italian patients,

with HLA-DR9 (DRB1*0901) in Chileans, and with HLA-DR3 (DRB1*0301) in Arab

populations.

chain,

is most common in Israeli Jews. Therefore, HLA-DR4 is not associated with RA in

this population. In certain groups of patients, there does not appear to be a

clear association between HLA-DR4-related epitopes and RA. Thus, nearly 75% of

African American RA patients do not have this genetic element. Moreover, there

is an association with HLA-DR10 (DRB1*1001) in Spanish and Italian patients,

with HLA-DR9 (DRB1*0901) in Chileans, and with HLA-DR3 (DRB1*0301) in Arab

populations.

Additional

genes in the HLA-D complex may also convey altered susceptibility to RA.

Certain HLA-DR alleles, including HLA-DR5 (DRB1*1101), HLA-DR2 (DRB1*1501),

HLA-DR3 (DRB1*0301), and HLA-DR7 (DRB1*0701), may protect against the

development of RA in that they tend to be found at lower frequency in RA

patients than in controls. Moreover, the HLA-DQ alleles, DQB1*0301 and

DQB1*0302, that are in linkage disequilibrium with HLA-DR4 and DQB1*0501, have

also been associated with RA. This has raised the possibility that HLA-DQ

alleles may represent the actual RA susceptibility genes, whereas specific

HLA-DR alleles may convey protection. In this model, the complement of HLA-DR

and DQ alleles determines RA susceptibility. Disease manifestations have also

been associated with HLA phenotype. Thus, early aggressive disease and

extraarticular manifestations are more frequent in patients with DRB1*0401 or

DRB1*0404, and more slowly progressive disease in those with DRB1*0101. The

presence of both DRB1*0401 and DRB1*0404 appears to increase the risk for both

aggressive articular and extraarticular disease. It has been estimated that HLA

genes contribute only a portion of the genetic susceptibility to RA. Thus genes

outside the HLA complex also contribute. These include genes controlling the

expression of the antigen receptor on T cells and both immunoglobulin heavy and

light chains. Moreover, polymorphisms in the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) ![]() and

the interleukin (IL) 10 genes are also associated with RA, as is a region on

chromosome 3 (3q13).

and

the interleukin (IL) 10 genes are also associated with RA, as is a region on

chromosome 3 (3q13).

Genetic

risk factors do not fully account for the incidence of RA, suggesting that

environmental factors also play a role in the etiology of the disease. This is

emphasized by epidemiologic studies in Africa that have indicated that climate

and urbanization have a major impact on the incidence and severity of RA in

groups of similar genetic background.

Etiology

The

cause of RA remains unknown. It has been suggested that RA might be a

manifestation of the response to an infectious agent in a genetically susceptible

host. Because of the worldwide distribution of RA, it has been hypothesized

that if an infectious agent is involved, the organism must be ubiquitous. A

number of possible causative agents have been suggested, including Mycoplasma,

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus, parvovirus, and rubella virus, but

convincing evidence that these or other infectious agents cause RA has not

emerged. The process by which an infectious agent might cause chronic

inflammatory arthritis with a characteristic distribution also remains a matter

of controversy. One possibility is that there is persistent infection of

articular structures or retention of microbial products in the synovial tissues

which generates a chronic inflammatory response. Alternatively, the microorganism

or response to the microorganism might induce an immune response to components

of the joint by altering its integrity and revealing antigenic peptides. In

this regard, reactivity to type II collagen and heat shock proteins has been

demonstrated. Another possibility is that the infecting microorganism might

prime the host to cross-reactive determinants expressed within the joint as a

result of "molecular mimicry." Recent evidence of similarity between

products of certain gram-negative bacteria and EBV and the HLA-DR4 molecule

itself has supported this possibility. Finally, products of infecting

microorganisms might induce the disease. Recent work has focused on the

possible role of "superantigens" produced by a number of

microorganisms, including staphylococci, streptococci and M. arthritidis.

Superantigens are proteins with the capacity to bind to HLA-DR molecules and

particular V![]() segments of the heterodimeric T cell receptor and stimulate specific T cells

expressing the V

segments of the heterodimeric T cell receptor and stimulate specific T cells

expressing the V![]() gene products (Chap. 305). The role of superantigens in the etiology of RA

remains speculative. Of all the potential environmental triggers, the only one

clearly associated with the development of RA is cigarette smoking

gene products (Chap. 305). The role of superantigens in the etiology of RA

remains speculative. Of all the potential environmental triggers, the only one

clearly associated with the development of RA is cigarette smoking

Pathology and Pathogenesis

Microvascular

injury and an increase in the number of synovial lining cells appear to be the

earliest lesions in rheumatoid synovitis. The nature of the insult causing this

response is not known. Subsequently, an increased number of synovial lining

cells is seen along with perivascular infiltration with mononuclear cells.

Before the onset of clinical symptoms, the perivascular infiltrate is

predominantly composed of myeloid cells, whereas in symptomatic arthritis, T

cells can also be found, although their number does not appear to correlate

with symptoms. As the process continues, the synovium becomes edematous and

protrudes into the joint cavity as villous projections.

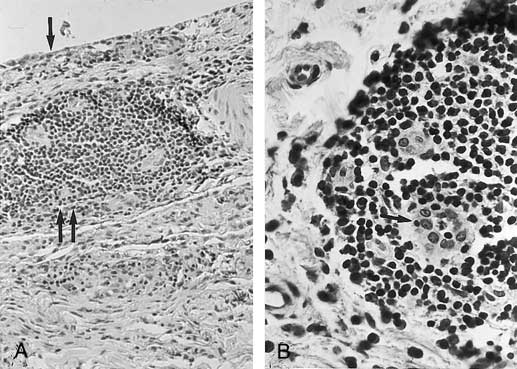

Light-microscopic

examination discloses a characteristic constellation of features, which include

hyperplasia and hypertrophy of the synovial lining cells; focal or segmental

vascular changes, including microvascular injury, thrombosis, and

neovascularization; edema; and infiltration with mononuclear cells, often

collected into aggregates around small blood vessels (Fig. 312-1). The

endothelial cells of the rheumatoid synovium have the appearance of high

endothelial venules of lymphoid organs and have been altered by cytokine

exposure to facilitate entry of cells into tissue. Rheumatoid synovial endothelial

cells express increased amounts of various adhesion molecules involved in this

process. Although this pathologic picture is typical of RA, it can also be seen

in a variety of other chronic inflammatory arthritides. The mononuclear cell

collections are variable in composition and size. The predominant infiltrating

cell is the T lymphocyte. CD4+ T cells predominate over CD8+ T cells and are

frequently found in close proximity to HLA-DR+ macrophages and dendritic cells.

Increased numbers of a separate population of T cells expressing the ![]()

![]() form

of the T cell receptor have also been found in the synovium, although they

remain a minor population there and their role in RA has not been delineated.

The major population of T cells in the rheumatoid synovium is composed of CD4+

memory T cells that form the majority of cells aggregated around postcapillary

venules. Scattered throughout the tissue are CD8+ T cells. Both populations

express the early activation antigen, CD69. Besides the accumulation of T

cells, rheumatoid synovitis is also characterized by the infiltration of

variable numbers of B cells and antibody-producing plasma cells. In advanced

disease, structures similar to germinal centers of secondary lymphoid organs

may be observed in the synovium. Both polyclonal immunoglobulin and the

autoantibody rheumatoid factor are produced within the synovial tissue, which

leads to the local formation of immune complexes. Finally, the synovial

fibroblasts in RA manifest evidence of activation in that they produce a number

of enzymes such as collagenase and cathepsins that can degrade components of

the articular matrix. These activated fibroblasts are particularly prominent in

the lining layer and at the interface with bone and cartilage. Osteoclasts are

also prominent at sites of bone erosion.

form

of the T cell receptor have also been found in the synovium, although they

remain a minor population there and their role in RA has not been delineated.

The major population of T cells in the rheumatoid synovium is composed of CD4+

memory T cells that form the majority of cells aggregated around postcapillary

venules. Scattered throughout the tissue are CD8+ T cells. Both populations

express the early activation antigen, CD69. Besides the accumulation of T

cells, rheumatoid synovitis is also characterized by the infiltration of

variable numbers of B cells and antibody-producing plasma cells. In advanced

disease, structures similar to germinal centers of secondary lymphoid organs

may be observed in the synovium. Both polyclonal immunoglobulin and the

autoantibody rheumatoid factor are produced within the synovial tissue, which

leads to the local formation of immune complexes. Finally, the synovial

fibroblasts in RA manifest evidence of activation in that they produce a number

of enzymes such as collagenase and cathepsins that can degrade components of

the articular matrix. These activated fibroblasts are particularly prominent in

the lining layer and at the interface with bone and cartilage. Osteoclasts are

also prominent at sites of bone erosion.

Figure 312-1: Histology of rheumatoid synovitis. A.

The characteristic features of rheumatoid inflammation with hyperplasia of the

lining layer (arrow) and mononuclear infiltrates in the sublining layer (double

arrow). B. A higher magnification of the largely CD4+ T cell

infiltrate around postcapillary venules (arrow).

The

rheumatoid synovium is characterized by the presence of a number of secreted

products of activated lymphocytes, macrophages, and fibroblasts. The local

production of these cytokines and chemokines appears to account for many of the

pathologic and clinical manifestations of RA. These effector molecules include

those that are derived from T lymphocytes such as interleukin IL-2, interferon

(IFN) ![]() ,

IL-6, IL-10, granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), TNF-

,

IL-6, IL-10, granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), TNF-![]() ,

transforming growth factor

,

transforming growth factor ![]() (TGF-

(TGF-![]() );

IL-13, IL-16, and IL-17; those originating from activated myeloid cells,

including IL-1, TNF-

);

IL-13, IL-16, and IL-17; those originating from activated myeloid cells,

including IL-1, TNF-![]() ,

IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, GM-CSF, macrophage CSF, platelet-derived growth

factor, insulin-like growth factor, and TGF-

,

IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, GM-CSF, macrophage CSF, platelet-derived growth

factor, insulin-like growth factor, and TGF-![]() ;

as well as those secreted by other cell types in the synovium, such as

fibroblasts and endothelial cells, including IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, GM-CSF, IL-15,

IL-16, IL-18, and macrophage CSF. The activity of these chemokines and

cytokines appears to account for many of the features of rheumatoid synovitis,

including the synovial tissue inflammation, synovial fluid inflammation,

synovial proliferation, and cartilage and bone damage, as well as the systemic

manifestations of RA. In addition to the production of effector molecules that

propagate the inflammatory process, local factors are produced that tend to

slow the inflammation, including specific inhibitors of cytokine action and

additional cytokines, such as TGF-

;

as well as those secreted by other cell types in the synovium, such as

fibroblasts and endothelial cells, including IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, GM-CSF, IL-15,

IL-16, IL-18, and macrophage CSF. The activity of these chemokines and

cytokines appears to account for many of the features of rheumatoid synovitis,

including the synovial tissue inflammation, synovial fluid inflammation,

synovial proliferation, and cartilage and bone damage, as well as the systemic

manifestations of RA. In addition to the production of effector molecules that

propagate the inflammatory process, local factors are produced that tend to

slow the inflammation, including specific inhibitors of cytokine action and

additional cytokines, such as TGF-![]() ,

which inhibits many of the features of rheumatoid synovitis including T cell

activation and proliferation, B cell differentiation, and migration of cells

into the inflammatory site.

,

which inhibits many of the features of rheumatoid synovitis including T cell

activation and proliferation, B cell differentiation, and migration of cells

into the inflammatory site.

These

findings have suggested that the propagation of RA is an immunologically

mediated event, although the original initiating stimulus has not been

characterized. One view is that the inflammatory process in the tissue is

driven by the CD4+ T cells infiltrating the synovium. Evidence for this

includes (1) the predominance of CD4+ T cells in the synovium; (2) the increase

in soluble IL-2 receptors, a product of activated T cells, in blood and

synovial fluid of patients with active RA; and (3) amelioration of the disease

by removal of T cells by thoracic duct drainage or peripheral lymphapheresis or

suppression of their function by drugs, such as cyclosporine or nondepleting

monoclonal antibodies to CD4. In addition, the association of RA with certain

HLA-DR or -DQ alleles, whose only known functions are to shape the repertoire

of CD4+ T cells during ontogeny in the thymus and bind and present antigenic

peptides to CD4+ T cells in the periphery, strongly implies a role for CD4+ T

cells in the pathogenesis of the disease. Finally, patients with established RA

who become infected with HIV also have been noted to improve, although this has

not been a uniform finding. Within the rheumatoid synovium, the CD4+ T cells

differentiate predominantly into Th1-like effector cells producing the

proinflammatory cytokine IFN-![]() and appear to be deficient in differentiation into Th2-like effector cells

capable of producing the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-4. As a result of the

ongoing secretion of IFN-

and appear to be deficient in differentiation into Th2-like effector cells

capable of producing the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-4. As a result of the

ongoing secretion of IFN-![]() without the regulatory influences of IL-4, macrophages are activated to produce

the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1 and TNF-

without the regulatory influences of IL-4, macrophages are activated to produce

the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1 and TNF-![]() and also increase expression of HLA molecules. Moreover, T lymphocytes express

surface molecules such as CD154 (CD40 ligand) and also produce a variety of

cytokines that promote B cell proliferation and differentiation into antibody-forming

cells and therefore also may promote local B cell stimulation. The resultant

production of immunoglobulin and rheumatoid factor can lead to immune-complex

formation with consequent complement activation and exacerbation of the

inflammatory process by the production of the anaphylatoxins, C3a and C5a, and

the chemotactic factor C5a. The tissue inflammation is reminiscent of delayed

type hypersensitivity reactions occurring in response to soluble antigens or

microorganisms, although it has become clear that the number of T cells

producing cytokines such as IFN-

and also increase expression of HLA molecules. Moreover, T lymphocytes express

surface molecules such as CD154 (CD40 ligand) and also produce a variety of

cytokines that promote B cell proliferation and differentiation into antibody-forming

cells and therefore also may promote local B cell stimulation. The resultant

production of immunoglobulin and rheumatoid factor can lead to immune-complex

formation with consequent complement activation and exacerbation of the

inflammatory process by the production of the anaphylatoxins, C3a and C5a, and

the chemotactic factor C5a. The tissue inflammation is reminiscent of delayed

type hypersensitivity reactions occurring in response to soluble antigens or

microorganisms, although it has become clear that the number of T cells

producing cytokines such as IFN-![]() is less than is found in typical delayed type hypersensitivity reactions,

perhaps owing to the large amount of reactive oxygen species produced locally

in the synovium that can dampen T cell function. It remains unclear whether the

persistent T cell activity represents a response to a persistent exogenous antigen

or to altered autoantigens such as collagen, immunoglobulin, or one of the heat

shock proteins, or perhaps both. Alternatively, it could represent persistent

responsiveness to activated autologous cells such as might occur as a result of

EBV infection or persistent response to a foreign antigen or superantigen in

the synovial tissue. Finally, rheumatoid inflammation could reflect persistent

stimulation of T cells by synovial-derived antigens that cross-react with

determinants introduced during antecedent exposure to foreign antigens or

infectious microorganisms.

is less than is found in typical delayed type hypersensitivity reactions,

perhaps owing to the large amount of reactive oxygen species produced locally

in the synovium that can dampen T cell function. It remains unclear whether the

persistent T cell activity represents a response to a persistent exogenous antigen

or to altered autoantigens such as collagen, immunoglobulin, or one of the heat

shock proteins, or perhaps both. Alternatively, it could represent persistent

responsiveness to activated autologous cells such as might occur as a result of

EBV infection or persistent response to a foreign antigen or superantigen in

the synovial tissue. Finally, rheumatoid inflammation could reflect persistent

stimulation of T cells by synovial-derived antigens that cross-react with

determinants introduced during antecedent exposure to foreign antigens or

infectious microorganisms.

Overriding

the chronic inflammation in the synovial tissue is an acute inflammatory

process in the synovial fluid. The exudative synovial fluid contains more

polymorphonuclear leukocytes than mononuclear cells. A number of mechanisms

play a role in stimulating the exudation of synovial fluid. Locally produced

immune complexes can activate complement and generate anaphylatoxins and

chemotactic factors. Local production, by a variety of cells, of chemokines and

cytokines with chemotactic activity as well as inflammatory mediators such as

leukotriene B4 and products of complement activation can attract

neutrophils. Moreover, many of these same agents can also stimulate the

endothelial cells of postcapillary venules to become more efficient at binding

circulating cells. The net result is the enhanced migration of

polymorphonuclear leukocytes into the synovial site. In addition, vasoactive

mediators such as histamine produced by the mast cells that infiltrate the

rheumatoid synovium may also facilitate the exudation of inflammatory cells

into the synovial fluid. Finally, the vasodilatory effects of locally produced

prostaglandin E2 may also facilitate entry of inflammatory cells

into the inflammatory site. Once in the synovial fluid, the polymorphonuclear

leukocytes can ingest immune complexes, with the resultant production of

reactive oxygen metabolites and other inflammatory mediators, further adding to

the inflammatory milieu. Locally produced cytokines and chemokines can

additionally stimulate polymorphonuclear leukocytes. The production of large

amounts of cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase pathway products of arachidonic acid

metabolism by cells in the synovial fluid and tissue further accentuates the

signs and symptoms of inflammation.

The

precise mechanism by which bone and cartilage destruction occurs has not been

completely resolved. Although the synovial fluid contains a number of enzymes

potentially able to degrade cartilage, the majority of destruction occurs in

juxtaposition to the inflamed synovium, or pannus, that spreads to cover the

articular cartilage. This vascular granulation tissue is composed of

proliferating fibroblasts, small blood vessels, and a variable number of

mononuclear cells and produces a large amount of degradative enzymes, including

collagenase and stromelysin, that may facilitate tissue damage. The cytokines

IL-1 and TNF-![]() play an important role by stimulating the cells of the pannus to produce

collagenase and other neutral proteases. These same two cytokines also activate

chondrocytes in situ, stimulating them to produce proteolytic enzymes that can

degrade cartilage locally and also inhibiting synthesis of new matrix

molecules. Finally, these two cytokines may contribute to the local

demineralization of bone by activating osteoclasts that accumulate at the site

of local bone resorption. Prostaglandin E2 produced by fibroblasts

and macrophages may also contribute to bone demineralization. The common final

pathway of bone erosion is likely to involve the activation of osteoclasts that

are present in large numbers at these sites. Systemic manifestations of RA can

be accounted for by release of inflammatory effector molecules from the

synovium. These include IL-1, TNF-

play an important role by stimulating the cells of the pannus to produce

collagenase and other neutral proteases. These same two cytokines also activate

chondrocytes in situ, stimulating them to produce proteolytic enzymes that can

degrade cartilage locally and also inhibiting synthesis of new matrix

molecules. Finally, these two cytokines may contribute to the local

demineralization of bone by activating osteoclasts that accumulate at the site

of local bone resorption. Prostaglandin E2 produced by fibroblasts

and macrophages may also contribute to bone demineralization. The common final

pathway of bone erosion is likely to involve the activation of osteoclasts that

are present in large numbers at these sites. Systemic manifestations of RA can

be accounted for by release of inflammatory effector molecules from the

synovium. These include IL-1, TNF-![]() ,

and IL-6, which account for many of the manifestations of active RA, including

malaise, fatigue, and elevated levels of serum acute-phase reactants. The

importance of TNF-

,

and IL-6, which account for many of the manifestations of active RA, including

malaise, fatigue, and elevated levels of serum acute-phase reactants. The

importance of TNF-![]() in producing these manifestations is emphasized by the prompt amelioration of

symptoms following administration of a monoclonal antibody to TNF-

in producing these manifestations is emphasized by the prompt amelioration of

symptoms following administration of a monoclonal antibody to TNF-![]() or a soluble TNF-

or a soluble TNF-![]() receptor Ig construct to patients with RA. In addition, immune complexes

produced within the synovium and entering the circulation may account for other

features of the disease, such as systemic vasculitis.

receptor Ig construct to patients with RA. In addition, immune complexes

produced within the synovium and entering the circulation may account for other

features of the disease, such as systemic vasculitis.

As

shown in Fig. 312-2, the pathology of RA evolves over the duration of this

chronic disease. The earliest event appears to be a nonspecific inflammatory

response initiated by an unknown stimulus and characterized by accumulation of

macrophages and other mononuclear cells within the sublining layer of the

synovium. The activity of these cells is demonstrated by the increased

appearance of macrophage-derived cytokines, including TNF-![]() ,

IL-1

,

IL-1![]() ,

and IL-6. Subsequently, activation of CD4+ T cells is induced, presumably in

response to antigenic peptides displayed by a variety of antigen-presenting

cells in the synovial tissue. The activated T cells are capable of producing

cytokines, especially IFN-

,

and IL-6. Subsequently, activation of CD4+ T cells is induced, presumably in

response to antigenic peptides displayed by a variety of antigen-presenting

cells in the synovial tissue. The activated T cells are capable of producing

cytokines, especially IFN-![]() ,

which amplify and perpetuate the inflammation. The presence of activated T

cells expressing CD154 (CD40 ligand) can induce polyclonal B cell stimulation

and the local production of rheumatoid factor. The cascade of cytokines

produced in the synovium activates a variety of cells in the synovium, bone,

and cartilage to produce effector molecules that can cause tissue damage

characteristic of chronic inflammation. It is important to emphasize that there

is no current way to predict the progress from one stage of inflammation to the

next, and once established, each can influence the other. Important features of

this model include the following: (1) the major pathologic events vary with

time in this chronic disease; (2) the time required to progress from one step

to the next may vary in different patients and the events, once established,

may persist simultaneously; (3) once established, the major pathogenic events

operative in an individual patient may vary at different times; and (4) the

process is chronic and reiterative, with successive events stimulating

progressive amplification of inflammation. These considerations have important

implications with regard to appropriate treatment.

,

which amplify and perpetuate the inflammation. The presence of activated T

cells expressing CD154 (CD40 ligand) can induce polyclonal B cell stimulation

and the local production of rheumatoid factor. The cascade of cytokines

produced in the synovium activates a variety of cells in the synovium, bone,

and cartilage to produce effector molecules that can cause tissue damage

characteristic of chronic inflammation. It is important to emphasize that there

is no current way to predict the progress from one stage of inflammation to the

next, and once established, each can influence the other. Important features of

this model include the following: (1) the major pathologic events vary with

time in this chronic disease; (2) the time required to progress from one step

to the next may vary in different patients and the events, once established,

may persist simultaneously; (3) once established, the major pathogenic events

operative in an individual patient may vary at different times; and (4) the

process is chronic and reiterative, with successive events stimulating

progressive amplification of inflammation. These considerations have important

implications with regard to appropriate treatment.

Figure 312-2: The progression of rheumatoid synovitis.

This figure depicts the evolution of the pathogenic mechanisms and ultimate

pathologic changes involved in the development of rheumatoid synovitis. The

stages of rheumatoid arthritis are proposed to be an initiation phase of

nonspecific inflammation, followed by an amplification phase resulting from T

cell activation, and finally a stage of chronic inflammation with tissue

injury. A variety of stimuli may initiate the initial phase of nonspecific

inflammation, which may last for a protracted period of time with no or

moderate symptoms. When activation of memory T cells in response to a variety

of peptides presented by antigen-presenting cells occurs in genetically

susceptible individuals, amplification of inflammation occurs with the

promotion of local rheumatoid factor production and enhanced capacity to

mediate tissue damage.

Clinical Manifestations

Onset

Characteristically,

RA is a chronic polyarthritis. In approximately two-thirds of patients, it

begins insidiously with fatigue, anorexia, generalized weakness, and vague

musculoskeletal symptoms until the appearance of synovitis becomes apparent.

This prodrome may persist for weeks or months and defy diagnosis. Specific

symptoms usually appear gradually as several joints, especially those of the

hands, wrists, knees, and feet, become affected in a symmetric fashion. In

approximately 10% of individuals, the onset is more acute, with a rapid

development of polyarthritis, often accompanied by constitutional symptoms,

including fever, lymphadenopathy, and splenomegaly. In approximately one-third

of patients, symptoms may initially be confined to one or a few joints. Although

the pattern of joint involvement may remain asymmetric in a few patients, a

symmetric pattern is more typical.

Signs and Symptoms of Articular Disease

Pain,

swelling, and tenderness may initially be poorly localized to the joints. Pain

in affected joints, aggravated by movement, is the most common manifestation of

established RA. It corresponds in pattern to the joint involvement but does not

always correlate with the degree of apparent inflammation. Generalized

stiffness is frequent and is usually greatest after periods of inactivity.

Morning stiffness of greater than 1-h duration is an almost invariable feature

of inflammatory arthritis and may serve to distinguish it from various

noninflammatory joint disorders. Notably, however, the presence of morning

stiffness may not reliably distinguish between chronic inflammatory and

noninflammatory arthritides, as it is also found frequently in the latter. The

majority of patients will experience constitutional symptoms such as weakness,

easy fatigability, anorexia, and weight loss. Although fever to 40°C occurs on

occasion, temperature elevation in excess of 38°C is unusual and suggests the

presence of an intercurrent problem such as infection.

Clinically,

synovial inflammation causes swelling, tenderness, and limitation of motion.

Warmth is usually evident on examination, especially of large joints such as

the knee, but erythema is infrequent. Pain originates predominantly from the

joint capsule, which is abundantly supplied with pain fibers and is markedly sensitive

to stretching or distention. Joint swelling results from accumulation of

synovial fluid, hypertrophy of the synovium, and thickening of the joint

capsule. Initially, motion is limited by pain. The inflamed joint is usually

held in flexion to maximize joint volume and minimize distention of the

capsule. Later, fibrous or bony ankylosis or soft tissue contractures lead to

fixed deformities.

Although

inflammation can affect any diarthrodial joint, RA most often causes symmetric

arthritis with characteristic involvement of certain specific joints such as

the proximal interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints. The distal

interphalangeal joints are rarely involved. Synovitis of the wrist joints is a

nearly uniform feature of RA and may lead to limitation of motion, deformity,

and median nerve entrapment (carpal tunnel syndrome). Synovitis of the elbow

joint often leads to flexion contractures that may develop early in the

disease. The knee joint is commonly involved with synovial hypertrophy, chronic

effusion, and frequently ligamentous laxity. Pain and swelling behind the knee

may be caused by extension of inflamed synovium into the popliteal space

(Baker's cyst). Arthritis in the forefoot, ankles, and subtalar joints can

produce severe pain with ambulation as well as a number of deformities. Axial

involvement is usually limited to the upper cervical spine. Involvement of the

lumbar spine is not seen, and lower back pain cannot be ascribed to rheumatoid

inflammation. On occasion, inflammation from the synovial joints and bursae of

the upper cervical spine leads to atlantoaxial subluxation. This usually

presents as pain in the occiput but on rare occasions may lead to compression

of the spinal cord.

With

persistent inflammation, a variety of characteristic joint changes develop.

These can be attributed to a number of pathologic events, including laxity of

supporting soft tissue structures; damage or weakening of ligaments, tendons,

and the joint capsule; cartilage degradation; muscle imbalance; and unopposed

physical forces associated with the use of affected joints. Characteristic

changes of the hand include (1) radial deviation at the wrist with ulnar

deviation of the digits, often with palmar subluxation of the proximal

phalanges ("Z" deformity); (2) hyperextension of the proximal

interphalangeal joints, with compensatory flexion of the distal interphalangeal

joints (swan-neck deformity); (3) flexion contracture of the proximal

interphalangeal joints and extension of the distal interphalangeal joints (boutonnière

deformity); and (4) hyperextension of the first interphalangeal joint and

flexion of the first metacarpophalangeal joint with a consequent loss of thumb

mobility and pinch. Typical joint changes may also develop in the feet,

including eversion at the hindfoot (subtalar joint), plantar subluxation of the

metatarsal heads, widening of the forefoot, hallux valgus, and lateral

deviation and dorsal subluxation of the toes.

Extraarticular Manifestations

RA

is a systemic disease with a variety of extraarticular manifestations. Although

these occur frequently, not all of them have clinical significance. However, on

occasion, they may be the major evidence of disease activity and source of

morbidity and require management per se. As a rule, these manifestations occur

in individuals with high titers of autoantibodies to the Fc component of

immunoglobulin G (rheumatoid factors).

Rheumatoid nodules develop in 20 to 30% of persons with RA. They

are usually found on periarticular structures, extensor surfaces, or other

areas subjected to mechanical pressure, but they can develop elsewhere,

including the pleura and meninges. Common locations include the olecranon

bursa, the proximal ulna, the Achilles tendon, and the occiput. Nodules vary in

size and consistency and are rarely symptomatic, but on occasion they break

down as a result of trauma or become infected. They are found almost invariably

in individuals with circulating rheumatoid factor. Histologically, rheumatoid

nodules consist of a central zone of necrotic material including collagen

fibrils, noncollagenous filaments, and cellular debris; a midzone of palisading

macrophages that express HLA-DR antigens; and an outer zone of granulation

tissue. Examination of early nodules has suggested that the initial event may

be a focal vasculitis. In some patients, treatment with methotrexate can

increase the number of nodules dramatically.

Clinical

weakness and atrophy of skeletal muscle are common. Muscle atrophy may be

evident within weeks of the onset of RA and is usually most apparent in

musculature approximating affected joints. Muscle biopsy may show type II fiber

atrophy and muscle fiber necrosis with or without a mononuclear cell

infiltrate.

Rheumatoid vasculitis (Chap. 317), which can affect nearly any organ

system, is seen in patients with severe RA and high titers of circulating

rheumatoid factor. Rheumatoid vasculitis is very uncommon in African Americans.

In its most aggressive form, rheumatoid vasculitis can cause polyneuropathy and

mononeuritis multiplex, cutaneous ulceration and dermal necrosis, digital

gangrene, and visceral infarction. While such widespread vasculitis is very

rare, more limited forms are not uncommon, especially in white patients with

high titers of rheumatoid factor. Neurovascular disease presenting either as a

mild distal sensory neuropathy or as mononeuritis multiplex may be the only

sign of vasculitis. Cutaneous vasculitis usually presents as crops of small

brown spots in the nail beds, nail folds, and digital pulp. Larger ischemic ulcers,

especially in the lower extremity, may also develop. Myocardial infarction

secondary to rheumatoid vasculitis has been reported, as has vasculitic

involvement of lungs, bowel, liver, spleen, pancreas, lymph nodes, and testes.

Renal vasculitis is rare.

Pleuropulmonary manifestations, which are more

commonly observed in men, include pleural disease, interstitial fibrosis,

pleuropulmonary nodules, pneumonitis, and arteritis. Evidence of pleuritis is

found commonly at autopsy, but symptomatic disease during life is infrequent.

Typically, the pleural fluid contains very low levels of glucose in the absence

of infection. Pleural fluid complement is also low compared with the serum

level when these are related to the total protein concentration. Pulmonary fibrosis

can produce impairment of the diffusing capacity of the lung. Pulmonary nodules

may appear singly or in clusters. When they appear in individuals with

pneumoconiosis, a diffuse nodular fibrotic process (Caplan's syndrome) may

develop. On occasion, pulmonary nodules may cavitate and produce a pneumothorax

or bronchopleural fistula. Rarely, pulmonary hypertension secondary to

obliteration of the pulmonary vasculature occurs. In addition to

pleuropulmonary disease, upper airway obstruction from cricoarytenoid arthritis

or laryngeal nodules may develop.

Clinically

apparent heart disease attributed to the rheumatoid process is rare, but

evidence of asymptomatic pericarditis is found at autopsy in 50% of cases.

Pericardial fluid has a low glucose level and is frequently associated with the

occurrence of pleural effusion. Although pericarditis is usually asymptomatic,

on rare occasions death has occurred from tamponade. Chronic constrictive

pericarditis may also occur.

RA

tends to spare the central nervous system directly, although vasculitis can

cause peripheral neuropathy. Neurologic manifestations may also result

from atlantoaxial or midcervical spine subluxations. Nerve entrapment secondary

to proliferative synovitis or joint deformities may produce neuropathies of

median, ulnar, radial (interosseous branch), or anterior tibial nerves.

The

rheumatoid process involves the eye in fewer than 1% of patients.

Affected individuals usually have long-standing disease and nodules. The two

principal manifestations are episcleritis, which is usually mild and transient,

and scleritis, which involves the deeper layers of the eye and is a more

serious inflammatory condition. Histologically, the lesion is similar to a

rheumatoid nodule and may result in thinning and perforation of the globe

(scleromalacia perforans). From 15 to 20% of persons with RA may develop

Sjögren's syndrome with attendant keratoconjunctivitis sicca.

Felty's syndrome consists of chronic RA, splenomegaly,

neutropenia, and, on occasion, anemia and thrombocytopenia. It is most common

in individuals with long-standing disease. These patients frequently have high

titers of rheumatoid factor, subcutaneous nodules, and other manifestations of

systemic rheumatoid disease. Felty's syndrome is very uncommon in African

Americans. It may develop after joint inflammation has regressed. Circulating

immune complexes are often present, and evidence of complement consumption may

be seen. The leukopenia is a selective neutropenia with polymorphonuclear

leukocyte counts of <1500 cells per microliter and sometimes <1000 cells

per microliter. Bone marrow examination usually reveals moderate

hypercellularity with a paucity of mature neutrophils. However, the bone marrow

may be normal, hyperactive, or hypoactive; maturation arrest may be seen.

Hypersplenism has been proposed as one of the causes of leukopenia, but

splenomegaly is not invariably found and splenectomy does not always correct

the abnormality. Excessive margination of granulocytes caused by antibodies to

these cells, complement activation, or binding of immune complexes may

contribute to granulocytopenia. Patients with Felty's syndrome have increased

frequency of infections usually associated with neutropenia. The cause of the

increased susceptibility to infection is related to the defective function of

polymorphonuclear leukocytes as well as the decreased number of cells.

Osteoporosis secondary to rheumatoid involvement is common

and may be aggravated by glucocorticoid therapy. Glucocorticoid treatment may

cause significant loss of bone mass, especially early in the course of therapy,

even when low doses are employed. Osteopenia in RA involves both juxtaarticular

bone and long bones distant from involved joints. RA is associated with a

modest decrease in mean bone mass and a moderate increase in the risk of

fracture. Bone mass appears to be adversely affected by functional impairment

and active inflammation, especially early in the course of the disease.

RA in the Elderly

The

incidence of RA continues to increase past age 60. It has been suggested that

elderly-onset RA might have a poorer prognosis, as manifested by more

persistent disease activity, more frequent radiographically evident

deterioration, more frequent systemic involvement, and more rapid functional

decline. Aggressive disease is largely restricted to those patients with high

titers of rheumatoid factor. By contrast, elderly patients who develop RA

without elevated titers of rheumatoid factor (seronegative disease) generally

have less severe, often self-limited disease.

Laboratory Findings

No

tests are specific for diagnosing RA. However, rheumatoid factors, which are

autoantibodies reactive with the Fc portion of IgG, are found in more than

two-thirds of adults with the disease. Widely utilized tests largely detect IgM

rheumatoid factors. The presence of rheumatoid factor is not specific for RA.

Rheumatoid factor is found in 5% of healthy persons. The frequency of

rheumatoid factor in the general population increases with age, and 10 to 20%

of individuals over 65 years old have a positive test. In addition, a number of

conditions besides RA are associated with the presence of rheumatoid factor.

These include systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren's syndrome, chronic liver

disease, sarcoidosis, interstitial pulmonary fibrosis, infectious

mononucleosis, hepatitis B, tuberculosis, leprosy, syphilis, subacute bacterial

endocarditis, visceral leishmaniasis, schistosomiasis, and malaria. In

addition, rheumatoid factor may appear transiently in normal individuals after

vaccination or transfusion and may also be found in relatives of individuals

with RA.

The

presence of rheumatoid factor does not establish the diagnosis of RA as the

predictive value of the presence of rheumatoid factor in determining a

diagnosis of RA is poor. Thus fewer than one-third of unselected patients with

a positive test for rheumatoid factor will be found to have RA. Therefore, the

rheumatoid factor test is not useful as a screening procedure. However, the

presence of rheumatoid factor can be of prognostic significance because

patients with high titers tend to have more severe and progressive disease with

extraarticular manifestations. Rheumatoid factor is uniformly found in patients

with nodules or vasculitis. In summary, a test for the presence of rheumatoid

factor can be employed to confirm a diagnosis in individuals with a suggestive

clinical presentation and, if present in high titer, to designate patients at

risk for severe systemic disease. A number of additional autoantibodies may be

found in patients with RA, including antibodies to filaggrin, citrulline,

calpastatin, components of the spliceosome (RA-33), and an unknown antigen, Sa.

Some of these may be useful in diagnosis in that they may occur early in the

disease before rheumatoid factor is present or may be associated with

aggressive disease.

Normochromic,

normocytic anemia is frequently present in active RA. It is thought to reflect

ineffective erythropoiesis; large stores of iron are found in the bone marrow.

In general, anemia and thrombocytosis correlate with disease activity. The

white blood cell count is usually normal, but a mild leukocytosis may be

present. Leukopenia may also exist without the full-blown picture of Felty's

syndrome. Eosinophilia, when present, usually reflects severe systemic disease.

The

erythrocyte sedimentation rate is increased in nearly all patients with active

RA. The levels of a variety of other acute-phase reactants including

ceruloplasmin and C-reactive protein are also elevated, and generally such

elevations correlate with disease activity and the likelihood of progressive

joint damage.

Synovial

fluid analysis confirms the presence of inflammatory arthritis, although none

of the findings is specific. The fluid is usually turbid, with reduced

viscosity, increased protein content, and a slightly decreased or normal

glucose concentration. The white cell count varies between 5 and 50,000/![]() L;

polymorphonuclear leukocytes predominate. A synovial fluid white blood cell

count >2000/

L;

polymorphonuclear leukocytes predominate. A synovial fluid white blood cell

count >2000/![]() L

with more than 75% polymorphonuclear leukocytes is highly characteristic of

inflammatory arthritis, although not diagnostic of RA. Total hemolytic

complement, C3, and C4 are markedly diminished in synovial fluid relative to

total protein concentration as a result of activation of the classic complement

pathway by locally produced immune complexes.

L

with more than 75% polymorphonuclear leukocytes is highly characteristic of

inflammatory arthritis, although not diagnostic of RA. Total hemolytic

complement, C3, and C4 are markedly diminished in synovial fluid relative to

total protein concentration as a result of activation of the classic complement

pathway by locally produced immune complexes.

Radiographic Evaluation

Early

in the disease, roentgenograms of the affected joints are usually not helpful

in establishing a diagnosis. They reveal only that which is apparent from

physical examination, namely, evidence of soft tissue swelling and joint

effusion. As the disease progresses, abnormalities become more pronounced, but

none of the radiographic findings is diagnostic of RA. The diagnosis, however,

is supported by a characteristic pattern of abnormalities, including the

tendency toward symmetric involvement. Juxtaarticular osteopenia may become

apparent within weeks of onset. Loss of articular cartilage and bone erosions

develop after months of sustained activity. The primary value of radiography is

to determine the extent of cartilage destruction and bone erosion produced by

the disease, particularly when one is monitoring the impact of therapy with

disease-modifying drugs or surgical intervention. Other means of imaging bones

and joints, including 99mTc bisphosphonate bone scanning and

magnetic resonance imaging, may be capable of detecting early inflammatory

changes that are not apparent from standard radiography but are rarely

necessary in the routine evaluation of patients with RA.

Clinical Course and Prognosis

The

course of RA is quite variable and difficult to predict in an individual

patient. Most patients experience persistent but fluctuating disease activity,

accompanied by a variable degree of joint abnormalities and functional

impairment. After 10 to 12 years, fewer than 20% of patients will have no

evidence of disability or joint abnormalities. Within 10 years, approximately

50% of patients will have work disability. A number of features are correlated

with a greater likelihood of developing joint abnormalities or disabilities.

These include the presence of more than 20 inflamed joints, a markedly elevated

erythrocyte sedimentation rate, radiographic evidence of bone erosions, the

presence of rheumatoid nodules, high titers of serum rheumatoid factor, the

presence of functional disability, persistent inflammation, advanced age at

onset, the presence of comorbid conditions, low socioeconomic status or

educational level, or the presence of HLA-DRB1*0401 or -DRB*0404. The presence

of one or more of these implies the presence of more aggressive disease with a

greater likelihood of developing progressive joint abnormalities and

disability. Persistent elevation of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate,

disability, and pain on longitudinal follow-up are good predictors of work

disability. Patients who lack these features have more indolent disease with a

slower progression to joint abnormalities and disability. The pattern of

disease onset does not appear to predict the development of disabilities.

Approximately 15% of patients with RA will have a short-lived inflammatory

process that remits without major disability. These individuals tend to lack

the aforementioned features associated with more aggressive disease.

Several

features of patients with RA appear to have prognostic significance. Remissions

of disease activity are most likely to occur during the first year. White

females tend to have more persistent synovitis and more progressively erosive

disease than males. Persons who present with high titers of rheumatoid factor,

C-reactive protein, and haptoglobin also have a worse prognosis, as do

individuals with subcutaneous nodules or radiographic evidence of erosions at

the time of initial evaluation. Sustained disease activity of more than 1

year's duration portends a poor outcome, and persistent elevation of

acute-phase reactants appears to correlate strongly with radiographic

progression. A large proportion of inflamed joints manifest erosions within 2

years, whereas the subsequent course of erosions is highly variable; however,

in general, radiographic damage appears to progress at a constant rate in

patients with RA. Foot joints are affected more frequently than hand joints.

Despite the decrease in the rate of progressive joint damage with time,

functional disability, which develops early in the course of the disease,

continues to worsen at the same rate, although the most rapid rate of

functional loss occurs within the first 2 years of disease.

The

median life expectancy of persons with RA is shortened by 3 to 7 years. Of the

2.5-fold increase in mortality rate, RA itself is a contributing feature in 15

to 30%. The increased mortality rate seems to be limited to patients with more

severe articular disease and can be attributed largely to infection and

gastrointestinal bleeding. Drug therapy may also play a role in the increased

mortality rate seen in these individuals. Factors correlated with early death

include disability, disease duration or severity, glucocorticoid use, age at

onset, and low socioeconomic or educational status.

Diagnosis

The

mean delay from disease onset to diagnosis is 9 months. This is often related

to the nonspecific nature of initial symptoms. The diagnosis of RA is easily

made in persons with typical established disease. In a majority of patients,

the disease assumes its characteristic clinical features within 1 to 2 years of

onset. The typical picture of bilateral symmetric inflammatory polyarthritis

involving small and large joints in both the upper and lower extremities with

sparing of the axial skeleton except the cervical spine suggests the diagnosis.

Constitutional features indicative of the inflammatory nature of the disease,

such as morning stiffness, support the diagnosis. Demonstration of subcutaneous

nodules is a helpful diagnostic feature. Additionally, the presence of

rheumatoid factor, inflammatory synovial fluid with increased numbers of

polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and radiographic findings of juxtaarticular bone

demineralization and erosions of the affected joints substantiate the

diagnosis.

The

diagnosis is somewhat more difficult early in the course when only

constitutional symptoms or intermittent arthralgias or arthritis in an

asymmetric distribution may be present. A period of observation may be

necessary before the diagnosis can be established. A definitive diagnosis of RA

depends predominantly on characteristic clinical features and the exclusion of

other inflammatory processes. The isolated finding of a positive test for rheumatoid

factor or an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, especially in an older

person with joint pains, should not itself be used as evidence of RA.

In

1987, the American College of Rheumatology developed revised criteria for the

classification of RA (Table 312-1). These criteria demonstrate a sensitivity of

91 to 94% and a specificity of 89% when used to classify patients with RA

compared with control subjects with rheumatic diseases other than RA. Although

these criteria were developed as a means of disease classification for

epidemiologic purposes, they can be useful as guidelines for establishing the

diagnosis. Failure to meet these criteria, however, especially during the early

stages of the disease, does not exclude the diagnosis. Moreover, in patients

with early arthritis, the criteria do not discriminate effectively between

patients who subsequently develop persistent, disabling, or erosive disease and

those who do not.

Table 312-1: The 1987 Revised Criteria for the

Classification of Rheumatoid Arthritis

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

![]() Treatment

Treatment

General Principles

The

goals of therapy of RA are (1) relief of pain, (2) reduction of inflammation,

(3) protection of articular structures, (4) maintenance of function, and (5)

control of systemic involvement. Since the etiology of RA is unknown, the

pathogenesis is not completely delineated, and the mechanisms of action of many

of the therapeutic agents employed are uncertain, therapy remains largely

empirical. None of the therapeutic interventions is curative, and therefore all

must be viewed as palliative, aimed at relieving the signs and symptoms of the

disease. The various therapies employed are directed at nonspecific suppression

of the inflammatory or immunologic process in the hope of ameliorating symptoms

and preventing progressive damage to articular structures.

Management

of patients with RA involves an interdisciplinary approach, which attempts to

deal with the various problems that these individuals encounter with functional

as well as psychosocial interactions. A variety of physical therapy modalities

may be useful in decreasing the symptoms of RA. Rest ameliorates symptoms and

can be an important component of the total therapeutic program. In addition,

splinting to reduce unwanted motion of inflamed joints may be useful. Exercise

directed at maintaining muscle strength and joint mobility without exacerbating

joint inflammation is also an important aspect of the therapeutic regimen. A

variety of orthotic and assistive devices can be helpful in supporting and

aligning deformed joints to reduce pain and improve function. Education of the

patient and family is an important component of the therapeutic plan to help

those involved become aware of the potential impact of the disease and make

appropriate accommodations in life-style to maximize satisfaction and minimize

stress on joints.

Medical

management of RA involves five general approaches. The first is the use of

aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and simple

analgesics to control the symptoms and signs of the local inflammatory process.

These agents are rapidly effective at mitigating signs and symptoms, but they

appear to exert minimal effect on the progression of the disease. Recently,

specific inhibitors of the isoform of cyclooxygenase (Cox) that is upregulated

at inflammatory sites (Cox-2) have been developed. Cox-2-specific inhibitors

(CSIs) have been shown to be as effective as classic NSAIDs, which inhibit both

isoforms of Cox, but to cause significantly less gastroduodenal ulceration. The

second line of therapy involves use of low-dose oral glucocorticoids. Although

low-dose glucocorticoids have been widely used to suppress signs and symptoms

of inflammation, recent evidence suggests that they may also retard the

development and progression of bone erosions. Intraarticular glucocorticoids

can often provide transient symptomatic relief when systemic medical therapy

has failed to resolve inflammation. The third line of agents includes a variety

of agents that have been classified as the disease-modifying or slow-acting

antirheumatic drugs. These agents appear to have the capacity to decrease

elevated levels of acute-phase reactants in treated patients and, therefore,

are thought to modify the inflammatory component of RA and thus its destructive

capacity. Recently, combinations of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

(DMARDs) have shown promise in controlling the signs and symptoms of RA. A

fourth group of agents are the TNF-![]() neutralizing agents, which have been shown to have a major impact on the signs

and symptoms of RA. A fifth group of agents are the immunosuppressive and

cytotoxic drugs that have been shown to ameliorate the disease process in some

patients. Additional approaches have been employed in an attempt to control the

signs and symptoms of RA. Substituting omega-3 fatty acids such as

eicosapentaenoic acid found in certain fish oils for dietary omega-6 essential

fatty acids found in meat has also been shown to provide symptomatic

improvement in patients with RA. A variety of nontraditional approaches have

also been claimed to be effective in treating RA, including diets, plant and

animal extracts, vaccines, hormones, and topical preparations of various sorts.

Many of these are costly, and none has been shown to be effective. However,

belief in their efficacy ensures their continued use by some patients.

neutralizing agents, which have been shown to have a major impact on the signs

and symptoms of RA. A fifth group of agents are the immunosuppressive and

cytotoxic drugs that have been shown to ameliorate the disease process in some

patients. Additional approaches have been employed in an attempt to control the

signs and symptoms of RA. Substituting omega-3 fatty acids such as

eicosapentaenoic acid found in certain fish oils for dietary omega-6 essential

fatty acids found in meat has also been shown to provide symptomatic

improvement in patients with RA. A variety of nontraditional approaches have

also been claimed to be effective in treating RA, including diets, plant and

animal extracts, vaccines, hormones, and topical preparations of various sorts.

Many of these are costly, and none has been shown to be effective. However,

belief in their efficacy ensures their continued use by some patients.

Drugs

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

Besides

aspirin, many NSAIDs are available to treat RA. As a result of the capacity of

these agents to block the activity of the Cox enzymes and therefore the

production of prostaglandins, prostacyclin, and thromboxanes, they have

analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antipyretic properties. In addition, the

agents may exert other anti-inflammatory effects. These agents are all

associated with a wide spectrum of toxic side effects. Some, such as gastric

irritation, azotemia, platelet dysfunction, and exacerbation of allergic

rhinitis and asthma, are related to the inhibition of cyclooxygenase activity,

whereas a variety of others, such as rash, liver function abnormalities, and

bone marrow depression, may not be. None of the NSAIDs has been shown to be

more effective than aspirin in the treatment of RA. However, these nonaspirin

drugs are associated with a lower incidence of gastrointestinal intolerance.

None of the newer NSAIDs appears to show significant therapeutic advantages

over the other available agents. In addition, there is no consistent advantage

of any of these newer agents over the others with respect to the incidence or

severity of toxic manifestations. Recent evidence indicates that two separate

enzymes, Cox-1 and -2, are responsible for the initial metabolism of

arachidonic acid into various inflammatory mediators. The former is

constitutively present in many cells and tissues, including the stomach and the

platelet, whereas the latter is specifically induced in response to

inflammatory stimuli. Inhibition of Cox-2 accounts for the anti-inflammatory

effects of NSAIDs, whereas inhibition of Cox-1 induces much of the

mechanism-based toxicity. As the currently available NSAIDs inhibit both

enzymes, therapeutic benefit and toxicity are intertwined. CSIs have now been

approved for the treatment of RA. Clinical trials have shown that CSIs suppress

the signs and symptoms of RA as effectively as classic Cox-nonspecific NSAIDs

but are associated with a significantly reduced incidence of gastroduodenal

ulceration. This suggests that CSIs might be considered instead of classic

Cox-nonspecific NSAIDs, especially in persons with increased risk of

NSAID-induced major upper gastrointestinal side effects, including persons over

65, those with a history of peptic ulcer disease, persons receiving

glucocorticoids or anticoagulants, or those requiring high doses of NSAIDs.

Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs

Clinical

experience has delineated a number of agents that appear to have the capacity

to alter the course of RA. This group of agents includes methotrexate, gold

compounds, D-penicillamine, the antimalarials, and sulfasalazine. Despite

having no chemical or pharmacologic similarities, in practice these agents

share a number of characteristics. They exert minimal direct nonspecific

anti-inflammatory or analgesic effects, and therefore NSAIDs must be continued

during their administration, except in a few cases when true remissions are

induced with them. The appearance of benefit from DMARD therapy is usually

delayed for weeks or months. As many as two-thirds of patients develop some

clinical improvement as a result of therapy with any of these agents, although

the induction of true remissions is unusual. In addition to clinical

improvement, there is frequently an improvement in serologic evidence of

disease activity, and titers of rheumatoid factor and C-reactive protein and

the erythrocyte sedimentation rate frequently decline. Moreover, emerging

evidence suggests that DMARDs actually retard the development of bone erosions

or facilitate their healing. Furthermore, developing evidence suggests that

early aggressive treatment with DMARDs may be effective at slowing the

appearance of bone erosions.

Which

DMARD should be the drug of first choice remains controversial, and trials have

failed to demonstrate a consistent advantage of one over the other. Despite

this, methotrexate has emerged as the DMARD of choice because of its relatively

rapid onset of action, its capacity to effect sustained improvement with

ongoing therapy, and the high level of patient retention on therapy. Each of

the DMARDs is associated with considerable toxicity, and therefore careful

patient monitoring is necessary. Toxicity of the various agents also becomes

important in determining the drug of first choice. Of note, failure to respond

or development of toxicity to one DMARD does not preclude responsiveness to

another. Thus, a similar percentage of RA patients who have failed to respond

to one DMARD will respond to another when it is given as the second

disease-modifying drug.

No

characteristic features of patients have emerged that predict responsiveness to

a DMARD. Moreover, the indications for the initiation of therapy with one of

these agents are not well defined, although recently the trend has been to

begin DMARD therapy early in the course of the disease, and data have begun to

emerge to support the conclusion that this approach may slow the development of

bone erosions, although this remains controversial.

The

folic acid antagonist methotrexate, given in an intermittent low dose (7.5 to 30

mg once weekly), is currently a frequently utilized DMARD. Most rheumatologists

recommend use of methotrexate as the initial DMARD, especially in individuals

with evidence of aggressive RA. Recent trials have documented the efficacy of

methotrexate and have indicated that its onset of action is more rapid than

other DMARDs, and patients tend to remain on therapy with methotrexate longer

than they remain on other DMARDs because of better clinical responses and less

toxicity. Long-term trials have indicated that methotrexate does not induce

remission but rather suppresses symptoms while it is being administered.

Maximal improvement is observed after 6 months of therapy, with little

additional improvement thereafter. Major toxicity includes gastrointestinal upset,

oral ulceration, and liver function abnormalities that appear to be

dose-related and reversible and hepatic fibrosis that can be quite insidious,

requiring liver biopsy for detection in its early stages. Drug-induced

pneumonitis has also been reported. Liver biopsy is recommended for individuals

with persistent or repetitive liver function abnormalities. Concurrent

administration of folic acid or folinic acid may diminish the frequency of some

side effects without diminishing effectiveness.

Glucocorticoid Therapy

Systemic

glucocorticoid therapy can provide effective symptomatic therapy in patients

with RA. Low-dose (<7.5 mg/d) prednisone has been advocated as useful

additive therapy to control symptoms. Moreover, recent evidence suggests that

low-dose glucocorticoid therapy may retard the progression of bone erosions.

Monthly pulses with high-dose glucocorticoids may be useful in some patients

and may hasten the response when therapy with a DMARD is initiated.

TNF-![]() neutralizing agents

neutralizing agents

Recently,

biologic agents that bind and neutralize TNF-![]() have become available. One of these is a TNF-

have become available. One of these is a TNF-![]() type II receptor fused to IgG1 (etanercept), and the second is a chimeric

mouse/human monoclonal antibody to TNF-

type II receptor fused to IgG1 (etanercept), and the second is a chimeric

mouse/human monoclonal antibody to TNF-![]() (infliximab). Clinical trials have shown that parenteral administration of

either TNF-

(infliximab). Clinical trials have shown that parenteral administration of